The Sad Story of "Chunguito"

Spanish

Along the rocky coasts of Chile lives, amongst other mammals, the Chungungo or Chinchimen

(pre-Columbian names), a small and timid otter of the Mustelid family, whose scientific name

is Lontra felina.

It is a species in grave danger of extinction. Being hard to observe, there

is not much scientific information to date that would allow better understanding of their

population, territorialness, family behaviour, feeding habits, mating and so on needed

to help the species.

Along the rocky coasts of Chile lives, amongst other mammals, the Chungungo or Chinchimen

(pre-Columbian names), a small and timid otter of the Mustelid family, whose scientific name

is Lontra felina.

It is a species in grave danger of extinction. Being hard to observe, there

is not much scientific information to date that would allow better understanding of their

population, territorialness, family behaviour, feeding habits, mating and so on needed

to help the species.

The Chungungo, known also as "Gato de Mar" (Sea Cat) because of its cat-like appearance, has a scarce population along the coast south of Peru and through all of Chile. Although it has no natural predators, it faces a great threat in Man, who has hunted it for decades for its wonderful pelt. Apart from the Sea Otter of North America, our Lontra felina is one of the last two surviving otter species that live mostly at sea.

The Story of a Special Chungungo

It was a warm morning, in the first days of the third month of the year of the new century, after a summer storm in Maitencillo. As the sea became calm again, it found me very glad to have undertaken my first beach project, called "Multicancha de Arena El Chungungo" ("Sports Fields of Chungungo Sands"). My long-standing interest in this wonderful marine mammal, that has inhabited the rocky coasts from time immemorial, meant that I had no doubt what to call this new coastal sports project .

That morning, a good neighbour went to the rescue of a small dying Chungungo injured by the gulls that already had opened the skin of its head, and remembered that he had heard of chungungos on a nearby beach. He called me, saying "You have a pack of chungungos on the beach". "How do you know?"', I asked, astonished. "I found one dying and you know all about them".

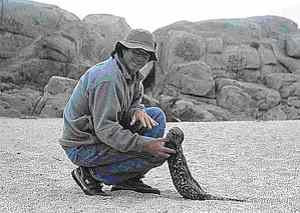

Without a second's hesitation, I ran there, and recieved "Chunguito" in my arms. He was unmoving, almost dead, and less than a month old. I then started a long hard fight for his life, with no prior knowledge of his needs, just using a computer and telephone, while he lay seriously ill on my bedspread.

Desperate, after tens of calls and virtual conferences looking for specilized vets, biologists and mammologists, I found first Yurgen Rotmass and then Gonzalo Medina. They provided my first lessons, but also a low opinion of Chunguito's chances of survival - taking into account his early age, maternal abandonment, infections and injury to the upper jaw, everything pained a discouraging picture. My great friend, Enrique Neumann, a vet in Puchuncav, who confessed that he knew nothing about chungungos, visited frequently to help and to observe the progress of "Chunguito's infected wounds It was already obvious that this was a suckling baby, with an incredible metabolism, requiring four daily feeds. I will never forget warning up a container of milk with a spoonful of butter, and using an nasal spray bottle, found forgotten in a drawer, to start feeding Chunguito. He seemed to be grateful as his vital signs and mobility increased. I was very happy too. I would be able to save him. Everything was a whirlwind. I ran to the phone, I returned to the samll patient, Anita came with lots of remedies, and was Chunguito's salvation, saying "this remedy one drop every two hours, the others once a day. . .", absorbing all my time and energies. Without thinking, despite the uncertainty, I was dedicated to saving Chunguito. Everyone said to me "It is very difficult, don't hope, he cannot live without his mother". Something inside me, however, as I watched him as he slept those first nights said that he could. Chunguito seemed to shout "I want to live!" /p>

April went by, and thanks to the care he recieved, Chunguito began slowly to heal. We unblocked his nose using liquid petroleum jelly, and Veterinarian Neumann applied a spray which quickly dried up his head wound. We began to take Chunguito down to the sea short in front of my house, where he enjoyed his natural environment. We had to manipulate his permanent teeth as they erupted to make sure he had the correct bite. He was massaged daily, after his bottle of milk.

We are happy with Chunguito. He has survived his abandonment and his wounds. His

vitality radiates through our lives. He moves more quickly every day, and his

predatory instincts are showing. Now we begin to prepare him for an independant life.

Strong and healthy, he goes down from the house to the sea every day. He chooses to

make his holt in a natural cave in the hill on which my house stands. I see him daily

cross the Avenida del Mar (a busy coastal road), and I fear he will be hit by a vehicle.

He shows his fine intelligence, however, watching from the roadside, and making his crossing

safely. That is not enough, and from our visitors, we get recommendations on how to protect

Chunguito from traffic. Cristin Gonzlez, a professional cameraman, brings an official

roadsign, with the silhouette of a small otter and the legend "Caution, Otter Crossing", and

puts it up on the Maitencillo road towards Santiago. We are happy, because the traffic

takes special care in this area.

We are happy with Chunguito. He has survived his abandonment and his wounds. His

vitality radiates through our lives. He moves more quickly every day, and his

predatory instincts are showing. Now we begin to prepare him for an independant life.

Strong and healthy, he goes down from the house to the sea every day. He chooses to

make his holt in a natural cave in the hill on which my house stands. I see him daily

cross the Avenida del Mar (a busy coastal road), and I fear he will be hit by a vehicle.

He shows his fine intelligence, however, watching from the roadside, and making his crossing

safely. That is not enough, and from our visitors, we get recommendations on how to protect

Chunguito from traffic. Cristin Gonzlez, a professional cameraman, brings an official

roadsign, with the silhouette of a small otter and the legend "Caution, Otter Crossing", and

puts it up on the Maitencillo road towards Santiago. We are happy, because the traffic

takes special care in this area.

Chunguito brings happiness to everyone who stops to see him. Grandfathers, fathers and children enjoy him, learning about his nature and behaviour. They get to know this animal, which, at best, they have heard of, but never seen, and learn that they have always lived along our coast, in places with dry rocks to establish their holts or "madrigueras".

Our friend grows and matures. We are in the presence of a strong, independent adult male. I see from my window that he is visited daily by a lady otter. They play in and out of the water and rocks. I do not doubt that they have mated. And, in my role as a father, I am moved. He disappears for a whole day, and reappears tired and hungry. I feed him and he sleeps for several hours. Obviously he has mated with "Chunguita". I dream of seeing them go away one day to form a family, perhaps near my rocks so I can go on protecting them. The sure thing is that they would only be dreams.

The ill-fated days of October arrive. After an active weekend, as Monday dawns, Chunguito does not appear as is his daily routine. Within minutes I am sure that something has happened to Chunguito! I first walk by the rocks, calling out in otter language, learnt during our wonderful coexistance. My steps come faster as I get more desperate. For hours I search, distressed, across all the southern shore area. It is already lunchtime, and no one has seen him. I ask if any dogs have been seen, or if there has been any disturbance. But nothing.

I increase my search in the afternoon, until someone gives me a clue: "There is a bloke near here that hunts chungungos". I cannot believe it - that there could be a hunter living so close to us. Breathing deeply, I go to the man, facing him while hiding my feelings. "Did you have any luck by the rocks" I ask him. He just sits there, so I ask "Are there any little animals with valuable skins that live by the water?". He says to me, quite calmly, "I caught one this morning". I almost die there are then, and with great difficulty ask him "What did you do with the body?". Now he is watching me suspiciously. In my head, everything comes together and I want to hit him, but by the skin of my teeth I do not, and leave.

On the way back, everything is confused. I repeat to mysefl time and time again: "Beast! how could you kill this history of love and giving without equal?" That night, I didn't sleep as pictures of Chunguito followed one another time and time again - never to see him again, never to see him play with Coipa, my sheepdog, who jealously protected him from other dogs - never to hear his song of love, which he sang when I caressed him from when he was tiny.

My friends, after nine months of a dream come true, my soul was destroyed. I was prepared to see him returned to a life in the sea, even to him being knocked down by a car, But, my God, not this way. Not thus. When the hunter was denounced before the Authorities, his skin was confiscated from him. It was on a wooden panel, drying in front of a fire.

This, then, was the end of Chunguito. As I write these lines, my heart tightens. I want everyone who reads this to know that this wonderful sea otter lives among us, and it all depends on us as to whether our children's children will get to know it. It wanted that all that one that reads them can know that this wonderful otter of the sea of Chile lives between us and who only of us it depends that the children of our children can get to know it.

For this reason, I desperately cry:

"LET US PROTECT THE CHUNGUNGOS OF THE COAST OF CHILE!"

Ricardo Correa began the Chinchimen Crusade which is working to protect the marine otters of Chile. His website is http://www.chinchimen.org /.

| Marine Otter |